Astronomers have discovered over 100 new alien worlds so far this year — some many light-years away from Earth — that showcase the vast diversity and drama of planetary systems across space.

The number of confirmed exoplanets — planets that don’t orbit the sun — has tipped 5,900, according to NASA, with thousands of additional candidates under review. All these worlds exist in our galaxy, though scientists believe they detected one planet outside the Milky Way in 2021.

This bounty is but a tiny sampling of the planets thought to exist throughout the universe. With hundreds of billions of galaxies, the cosmos probably sparkles with many trillions of stars. And if most stars have one or more orbiting planets — well, it’s hard to comprehend with our feeble human brains. After all, our own solar system has eight full-fledged planets (apologies, Pluto) — and possibly even more awaiting discovery.

No two exoplanets are alike, each harboring its own distinct chemistry and conditions. Getting to know these worlds is easier now with the powerful James Webb Space Telescope. The observatory, a collaboration of NASA and its European and Canadian counterparts, spends about a quarter of its time on exoplanets. By studying their atmospheres, scientists can learn a great deal, including whether a world could be habitable.

Webb is embarking on a massive study of rocky worlds outside the solar system, specifically to learn whether exoplanets orbiting near cool red dwarf stars could have air. The campaign, first reported by Mashable, will take a closer look at a dozen nearby-ish exoplanets.

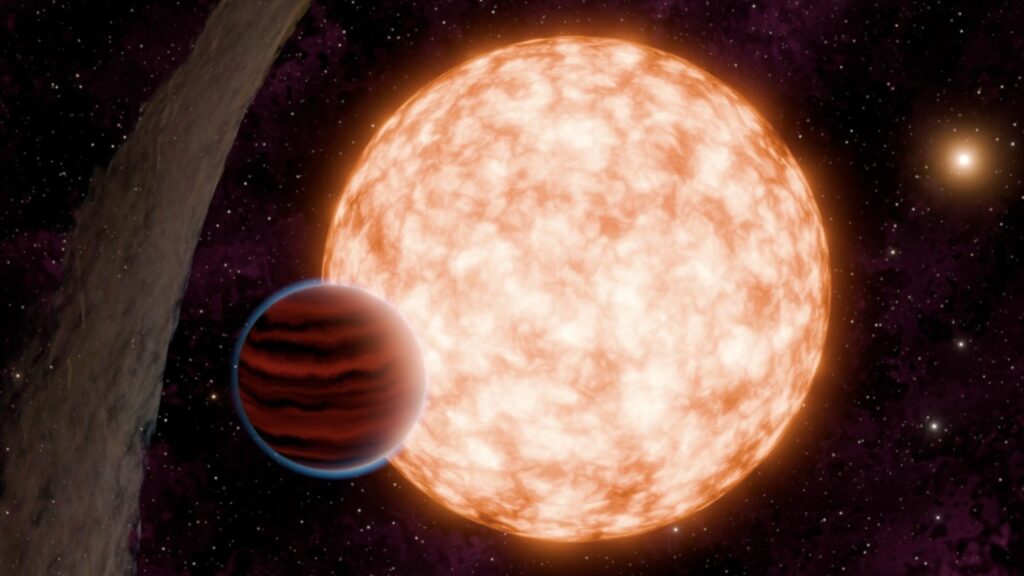

Credit: Jose-Luis Olivares / MIT illustration

BD+05 4868 Ab

Astronomers have discovered a planet with a comet-like tail stretching more than 5.5 million miles. The rocky exoplanet, BD+05 4868 Ab, orbits a star 140 light-years away in the constellation Pegasus. An MIT-led team of researchers detected this world’s tail, made of sand-sized particles, when it blocked some of the star’s light, causing uneven dimming during each pass.

BD+05 4868 Ab, found by NASA’s TESS mission, is about the size of Mercury and orbits its star every 30.5 hours. At roughly 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, the planet appears to be shedding material — about one Mount Everest’s worth per orbit — that becomes its tail. Scientists plan to follow-up with Webb to study its composition.

Proxima b

Proxima b, the closest Earth-size exoplanet, likely cannot support life, according to a new study. Though the world orbits within a sweet spot of its star system where liquid water might be possible to exist on its surface, scientists now believe its host star — Proxima Centauri — is far too hostile.

The star, about four light-years away, blasts the planet with extreme space weather that would likely strip away an atmosphere. Using 50 hours of observations with the ALMA telescope in Chile, researchers recorded 463 powerful stellar flares.

WASP-127b

Astronomers spotted ferocious winds whipping around WASP-127b — the likes of which they’ve never seen before. On the gas giant, a jet stream races around the planet’s equator at 20,500 mph. That’s almost 19 times faster than the gusts on Neptune, the strongest winds in the solar system.

Using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, scientists studied the planet’s atmosphere from 520 light-years away. They found signs of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and shifting temperatures across vast regions.

K2-18b

The scientists who brought us the tenuous discovery of a potential water world with signs of life last year have come back with new data they say strengthens their case. Exoplanet K2-18b — a so-called Hycean world because it may have a hydrogen-rich atmosphere over a global ocean — has a strong signal for dimethyl sulfide or a similar gas, the researchers said. On Earth, those chemicals are made by living things like microscopic algae.

But the follow-up study of the planet 124 light-years away has only increased the controversy, driving many scientists unaffiliated with the team to speak out against it. The bulk of that frustration comes from how the team has communicated its findings to the public, suggesting the group is perhaps closer to discovering life beyond Earth than it really is.

Credit: Ellis Bogat illustration

Gaia-4b

The European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft has had its first independent success using the so-called “wobble” technique to find new worlds. The method looks for subtle jitters in stars that can be caused by a planet’s gravity tugging on them.

The giant planet, Gaia-4b, is 12 times heavier than Jupiter and 244 light-years away, orbiting a tiny star just 64 percent the sun’s mass. Follow-up observations confirmed the discovery, marking a major milestone for Gaia’s planet-hunting mission.

YSES-1b and YSES-1c

Scientists used Webb to capture rare direct images of two young exoplanets, YSES-1b and YSES-1c, orbiting a star over 300 light-years away. YSES-1c shows dark, silicate clouds made of ultra-fine rock grains, and YSES-1b features a glowing dust disk — perhaps only the third of its kind ever observed — that may host a moon nursery.

These gas giants, each five to 15 times Jupiter’s mass, orbit a young, sun-like star, albeit at extreme distances. The new infrared images have offered a deep look into the chaotic early stages of planet and moon formation.